Extending the AI Periodic Table: Two Missing Elements for the Semantic AI Era

Just as you wouldn't build a house without blueprints, you shouldn't build AI guardrails without a DSL that precisely defines acceptable behavior.

Just as you wouldn't build a house without blueprints, you shouldn't build AI guardrails without a DSL that precisely defines acceptable behavior.

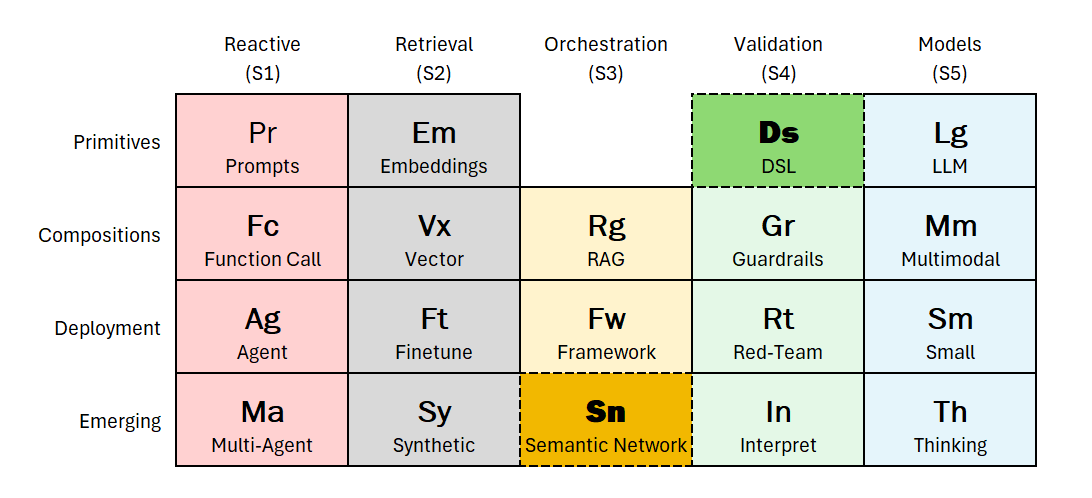

A proposed extension to IBM's Martin Keen framework with Domain-Specific Languages (Ds) and Semantic Networks (Sn)

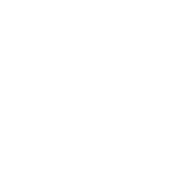

IBM Master Inventor Martin Keen recently introduced a conceptual framework that brought order to the chaos of AI terminology: the AI Periodic Table. Like Mendeleev's original, Keen's table organizes the building blocks of modern AI systems along two axes—maturity stages (rows) and functional families (columns)—revealing the hidden dependencies and compositional patterns that underlie everything from simple chatbots to sophisticated agentic systems.

The elegance of Keen's model lies in its predictive power. Just as the chemical periodic table revealed gaps where undiscovered elements should exist, Keen's framework exposes structural vacancies in our current understanding of AI architecture. Two cells, in particular, demand attention: Primitives/Validation and Emerging/Orchestration. These positions represent critical capabilities that are already reshaping production AI systems but have not yet been formally recognized in the canonical taxonomy.

This article proposes two extensions to the AI Periodic Table:

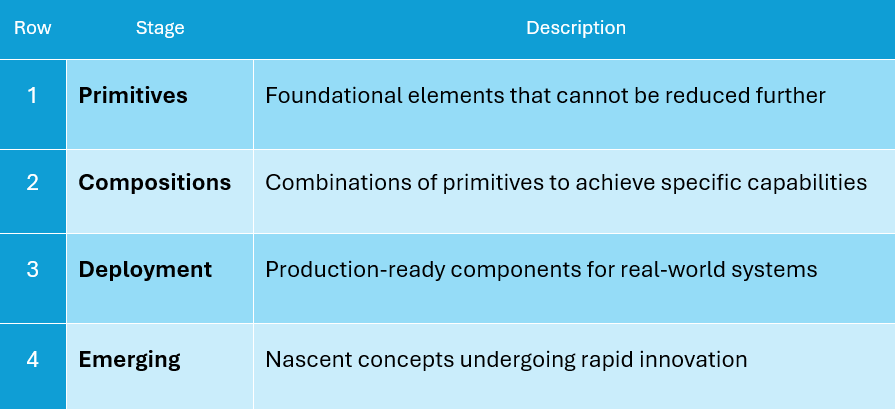

Keen's table organizes AI components across four rows representing maturity stages:

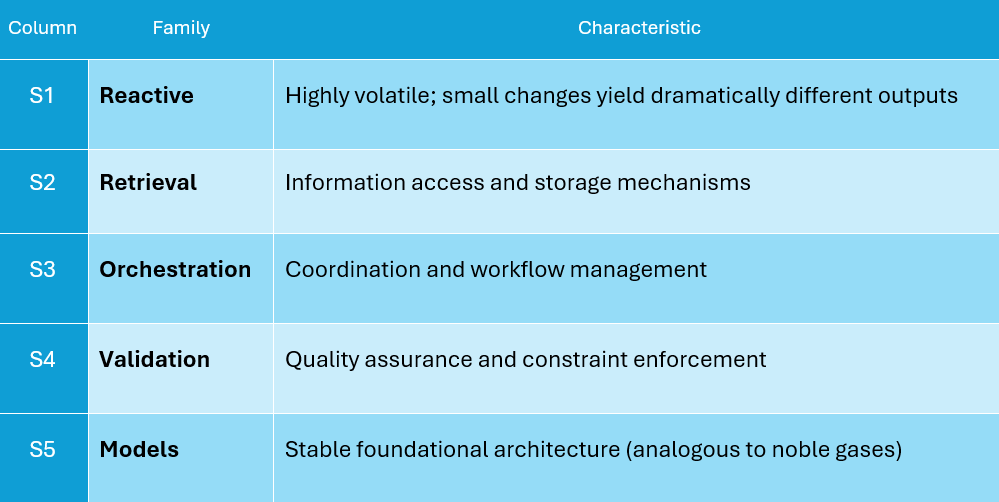

These intersect with five functional families:

Keen observed that elements exhibit varying degrees of "reactivity"—prompts are highly reactive ("you change one word and you get completely different output"), while LLMs in the Models column behave more like noble gases: stable and foundational. This insight reveals why AI systems are so difficult to debug: reactive elements amplify small perturbations through the system.

The original table positions Guardrails (Gr) as the composition-level validation mechanism and Red-Teaming (Rt) at the deployment tier. Interpretability (In) occupies the emerging/validation cell. But what serves as the primitive for validation? The original framework leaves this cell conspicuously empty.

Similarly, while RAG (Rg) handles orchestration at the composition level and Frameworks (Fw) at deployment, the emerging tier for orchestration contains no recognized element—a gap that fails to capture the current explosion of semantic coordination approaches.

Position: Primitives/Validation (Row 1, Column S4)

Symbol: Ds

Classification: Validation Primitive

Domain-Specific Languages are formal syntaxes designed for specific problem domains that enforce structural constraints, enable automated validation, and provide deterministic behavior—qualities that stand in direct contrast to the probabilistic nature of LLMs.

The Validation column houses elements that constrain AI behavior: Guardrails filter outputs, Red-Teaming stress-tests systems, and Interpretability explains decisions. What these share is a commitment to verification—ensuring AI systems do what we intend.

DSLs are the atomic unit of this verification capability. They provide:

Consider the challenge of prompt injection. Natural language prompts are inherently ambiguous and susceptible to adversarial manipulation. A DSL-based approach—exemplified by NVIDIA's NeMo Guardrails—allows developers to define conversational policies in a domain-specific syntax that compilers can verify. The DSL enforces constraints that no amount of clever prompting can circumvent.

The convergence of DSLs and AI validation is already visible:

Impromptu (built on Langium) demonstrates how DSLs can specify prompts in a platform-independent way while generating validators that automatically assess whether LLM outputs meet specifications. The DSL defines traits (e.g., "ironic," "formal," "technical") and generates test harnesses that invoke secondary models to verify compliance.

NeMo Guardrails provides a programmable DSL for runtime safety policy enforcement. Rather than relying on statistical classifiers that might miss edge cases, developers specify exactly what topics are permitted, what conversational flows are valid, and what responses are acceptable—rules that execute deterministically regardless of what the LLM "wants" to do.

Microsoft's DSL-Copilot research shows how DSL compilers can participate in validation loops: the LLM generates DSL code, the DSL's parser validates syntax and semantics, and any errors feed back for correction. The process iterates until output is both syntactically valid and semantically acceptable.

TypeFox's work with Langium demonstrates how semiformal DSLs can blend natural language flexibility with formal verification, creating what they call "precise interfaces" that guide AI behavior more reliably than pure prompt engineering.

Unlike prompts (highly reactive) or LLMs (inert), DSLs occupy a middle ground. A DSL specification changes less frequently than prompts but requires explicit modification to evolve—it cannot "drift" as model weights shift. This makes DSLs a stabilizing primitive that anchors the more volatile elements around them.

Just as Embeddings (Em) compose with other primitives to form Vector databases (Vx) and ultimately RAG (Rg), DSLs compose to form Guardrails (Gr) and enable Red-Teaming (Rt). The dependency is clear: you cannot build robust guardrails without a formal language to specify what "robust" means. Natural language policies are ambiguous; DSL policies are precise.

Position: Emerging/Orchestration (Row 4, Column S3)

Symbol: Sn

Classification: Emerging Orchestration Primitive

Semantic Networks are structured representations of knowledge as interconnected nodes (concepts) and edges (relationships) that enable AI systems to reason about meaning, context, and dependencies across distributed components.

The Orchestration column houses elements that coordinate AI components: RAG connects retrieval to generation, and Frameworks provide the scaffolding for production systems. At the emerging tier, we need an element that captures how meaning itself becomes the coordination mechanism.

Current multi-agent systems (Ma) represent one emerging orchestration pattern, but they focus on agent collaboration rather than the semantic substrate that makes collaboration possible. Semantic Networks address a different problem: how do distributed AI components maintain coherent understanding across interactions?

Consider a multi-agent system where Agent A generates a policy identifier, Agent B must interpret that identifier in context, and Agent C must validate compliance. Without a shared semantic network, each agent operates on its own interpretation. With one, the meaning of "policy identifier" is fixed by its relationships to other concepts—customer profiles, compliance rules, regulatory frameworks—and all agents reason over the same semantic graph.

The integration of semantic networks with LLMs represents one of the most significant architectural shifts in contemporary AI:

Knowledge Graphs as Memory — Unlike vector stores that retrieve similar content, knowledge graphs retrieve structured relationships. When an agent queries "what prerequisites exist for Task B?", the knowledge graph returns a dependency subgraph, not a ranked list of embedding matches. This enables planning that respects logical constraints.

Graph-RAG — Combining traditional RAG with knowledge graph traversal creates hybrid retrieval that provides both the "skeletal structure of knowledge" (who-what-how relationships) and the "flesh" (detailed descriptions, raw text). This architecture, now being implemented in platforms like ZBrain, represents the operationalization of semantic networks in production AI.

Semantic Kernel — Microsoft's agent framework explicitly incorporates knowledge graphs as coordination mechanisms. Agents don't just pass messages; they query and update shared semantic state. The graph becomes the persistent memory that spans agent sessions and enables long-horizon planning.

6G Native-AI Networks — Research on next-generation telecommunications demonstrates semantic networks operating at the infrastructure level, where "semantic resource orchestration" allows agents to form temporary sub-networks, share capabilities through semantic descriptions, and coordinate through meaning rather than data exchange.

Semantic Networks exhibit low reactivity—relationships between concepts change slowly relative to prompt variations or model outputs. Adding a new node (a new concept) or edge (a new relationship) is an explicit operation with traceable provenance. This stability makes semantic networks suitable for representing organizational knowledge, regulatory requirements, and domain ontologies that should not fluctuate with each API call.

Semantic Networks compose with Multi-Agent systems (Ma) to enable what might be called "semantic coordination"—agents that reason over shared conceptual graphs rather than passing opaque messages. They also compose with Frameworks (Fw) to provide the memory layer that persists across invocations.

With these additions, the AI Periodic Table gains two new elements that fill previously empty cells:

The extended table reveals new "molecular" patterns for AI system design:

Validated Agent Pattern (Ag + Ds + Gr)

Agents that operate within DSL-defined constraints, with guardrails generated from formal specifications rather than heuristic rules.

Semantic Agentic RAG (Sn + Ma + Rg)

Multi-agent systems that coordinate through shared knowledge graphs, retrieving not just relevant documents but structured relationship data.

Formal Reasoning Chain (Ds + Th + Sn)

"Thinking" models (like o1) operating over DSL-validated logic, with conclusions traced through semantic networks for interpretability.

Trustworthy Enterprise AI (Ds + Gr + Rt + In)

A complete validation stack where DSLs define policies, guardrails enforce them, red-teaming probes for violations, and interpretability explains decisions—all grounded in formal specifications rather than statistical correlations.

The presence of Ds in the primitive layer suggests that production AI systems should establish formal specifications before implementing guardrails. Just as you wouldn't build a house without blueprints, you shouldn't build AI guardrails without a DSL that precisely defines acceptable behavior.

The Sn element at the emerging tier indicates that knowledge graphs are not yet fully mature for AI orchestration—but the direction is clear. Research investment in graph-enhanced reasoning, semantic retrieval, and structured agent memory will pay dividends as these approaches move toward deployment maturity.

When evaluating AI products, ask which elements they utilize. A system that claims "guardrails" but lacks any DSL foundation may be implementing heuristic filters rather than formal constraints. A system claiming "semantic understanding" without knowledge graph infrastructure may be conflating embedding similarity with genuine conceptual reasoning.

Martin Keen's AI Periodic Table provides a powerful lens for understanding how AI systems are composed. By extending it with Domain-Specific Languages (Ds) as the validation primitive and Semantic Networks (Sn) as the emerging orchestration element, we gain a more complete picture of the forces shaping production AI.

The periodic table metaphor reminds us that elements combine according to predictable rules. Knowing which elements are available—and which are still emerging—helps us design systems that leverage proven patterns while anticipating where the field is heading.

Just as chemists use the periodic table to predict reactions, AI architects can use this extended framework to predict which component combinations will yield stable, useful systems—and which will prove volatile, unreliable, or incomplete.

Comments welcome.

I am an Information Architect and Software Engineer specializing in language engineering and semantic AI systems. My work focuses on applying Domain-Specific Languages to human-in-the-loop AI workflows.