MCP Needs a Type System, Part 2: Building the Contract Layer

Tool descriptions suggest constraints to LLMs, but suggestions aren't guarantees. So what would formal MCP contracts actually look like?

Tool descriptions suggest constraints to LLMs, but suggestions aren't guarantees. So what would formal MCP contracts actually look like?

In Part 1, we examined six MCP security incidents—from remote code execution to cross-tenant data exposure—and found a common thread: boundaries that everyone assumed existed, but no one enforced. JSON Schema validates structure, not semantics. Tool descriptions suggest constraints to LLMs, but suggestions aren't guarantees. The question we left with: what would formal MCP contracts actually look like?

Consider what we're asking JSON Schema to do:

{

"name": "execute_query",

"description": "Run a SQL query. Only SELECT statements allowed.",

"parameters": {

"query": { "type": "string" }

}

}The constraint lives in a description field—plain English that an LLM might respect, might misunderstand, or might ignore entirely when prompted creatively. The schema validates that query is a string. It cannot validate that the string contains only SELECT statements.

Now consider the alternative:

tool execute_query {

parameter query: SqlQuery {

constraint: SelectOnly

tables: ["users", "orders", "products"]

forbidden: ["DELETE", "DROP", "TRUNCATE", "UPDATE", "INSERT"]

}

}This isn't documentation. It's a specification—one that can be:

The description didn't disappear. It became structured—and structure is enforceable.

This is the premise of the Contract DSL approach: move security-critical constraints out of natural language and into a formal language designed for the job.

The security community has responded to these incidents with familiar prescriptions: input sanitization, rate limiting, SIEM integration, human-in-the-loop approvals. These controls are necessary but insufficient. They treat symptoms without addressing the root cause.

MCP's fundamental problem is that it lacks a formal contract language for expressing what tools should and shouldn't do. JSON Schema validates shapes. Descriptions suggest behaviors. Neither constitutes a machine-verifiable contract.

What would contract-level type safety actually look like?

Instead of string paths with documentation, a contract language could express:

resource FileAccess {

workspace_root: Path

constraint readable_file(p: Path) {

p.starts_with(workspace_root) and p.is_file()

}

constraint writable_file(p: Path) {

readable_file(p) and not p.extension in [".exe", ".sh", ".bat"]

}

}

Tools would then declare which capabilities they require:

tool edit_document {

requires FileAccess with writable_file

param document: writable_file

param content: string

}A runtime monitor could verify that all file operations respect these constraints—not as a description, but as enforced behavior.

The GitHub MCP breach exploited overly-broad PAT scopes. A contract language could make scope boundaries explicit and verifiable:

scope github_public {

allows read_issue(repo where repo.visibility = "public")

allows read_comment(repo where repo.visibility = "public")

}

scope github_private {

extends github_public

allows read_issue(repo where user.has_access(repo))

allows read_repository(repo where user.has_access(repo))

}

tool get_issue {

requires github_public or github_private

param repo: Repository

param issue_number: int

}Tool invocations would then be checked against granted scopes, catching privilege escalation attempts before execution.

The WhatsApp exfiltration worked because nothing prevented data from flowing across trust boundaries. Contract-level type safety could express:

sensitivity WhatsApp = HIGH

sensitivity PublicAPI = LOW

constraint no_exfiltration {

data.sensitivity(source) <= data.sensitivity(destination)

}

tool send_to_webhook {

param data: any

param url: URL

enforces no_exfiltration between (data, url)

}This would make data flow policies machine-checkable rather than implicit in natural language descriptions.

Building a contract language sounds like a multi-year research project. It's not—if you have the right foundation.

Langium is an open-source language engineering toolkit that generates complete TypeScript-based language servers from grammar definitions. It produces typed abstract syntax trees, provides LSP integration for IDE support, and runs anywhere JavaScript runs: VS Code extensions, CLI tools, web applications, CI/CD pipelines.

Here's why Langium is uniquely suited for MCP contract definition:

Langium grammars produce TypeScript interfaces for the abstract syntax tree. When you define:

Tool:

'tool' name=ID '{'

('requires' requirements+=Capability (',' requirements+=Capability)*)?

('param' params+=Parameter)*

('enforces' constraints+=Constraint)*

'}';

Capability:

name=ID ('with' bound=ConstraintRef)?;Langium generates interfaces like:

interface Tool {

name: string;

requirements: Capability[];

params: Parameter[];

constraints: Constraint[];

}Your contract validation code operates on strongly-typed structures, not string-parsed JSON. Typos become compile errors. Structural inconsistencies get caught at build time.

MCP tools reference other tools, scopes reference other scopes, constraints reference capabilities. Langium handles cross-reference resolution automatically—including across multiple files in a workspace. When an MCP server declares it requires FileAccess, Langium's linking infrastructure verifies that FileAccess exists and has the right structure.

This enables compositional contract definitions where organizations build reusable capability libraries that tool authors reference.

Langium provides hooks for semantic validation that go beyond syntax checking:

export function registerValidationChecks(checks: ValidationChecks) {

checks.register('Tool', (tool, accept) => {

for (const param of tool.params) {

if (param.type.name === 'Path' && !tool.requirements.some(r => r.name === 'FileAccess')) {

accept('error', 'Tool uses Path parameter but does not require FileAccess', {

node: param

});

}

}

});

}These validations appear as IDE errors in VS Code, CLI errors in build pipelines, and runtime errors in contract enforcement. The same logic protects developers writing contracts and operators deploying MCP servers.

Because Langium implements the Language Server Protocol, your contract DSL automatically gets:

Security teams defining organizational policies get the same editing experience as developers writing application code. This matters because security policies that are hard to write correctly don't get written correctly.

Here's how a Langium-based contract layer integrates with existing MCP infrastructure:

Tool authors write contract definitions alongside their MCP server implementations:

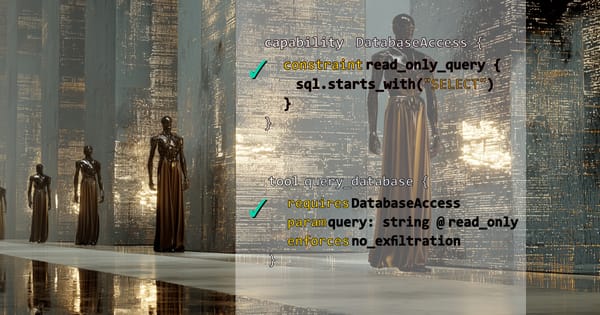

// tools/database.contracts

capability DatabaseAccess {

connection_string: secret

constraint read_only_query(sql: string) {

sql.lowercase.starts_with("select") and

not sql.lowercase.contains("drop") and

not sql.lowercase.contains("delete") and

not sql.lowercase.contains("update") and

not sql.lowercase.contains("insert")

}

}

tool query_database {

requires DatabaseAccess with read_only_query

param query: string @ read_only_query

returns json

}The @ annotation binds the parameter to a constraint. The Langium-generated validator ensures the constraint is applicable to the parameter type.

During build, the contract compiler:

The generated validators become middleware in the MCP server:

import { createContractValidator } from './generated/database.contracts';

server.on('tools/call', async (request) => {

const validator = createContractValidator(request.tool);

const violations = validator.check(request.arguments);

if (violations.length > 0) {

return {

error: {

code: 'CONTRACT_VIOLATION',

message: violations[0].message,

data: { violations }

}

};

}

// Proceed with tool execution

});Constraint violations are caught before tool logic executes—not as an LLM suggestion, but as a programmatic enforcement.

MCP clients can fetch and display contract manifests, giving users visibility into what tools are actually permitted to do:

{

"tool": "query_database",

"capabilities": {

"DatabaseAccess": {

"constraints": ["read_only_query"],

"description": "Allows SELECT queries only"

}

},

"verified": "2025-02-01T10:30:00Z",

"signature": "0x..."

}Security teams can now audit tool permissions mechanically rather than reading descriptions and hoping they're accurate.

Enterprises deploying MCP servers can define organizational policy contracts:

// policies/data-classification.contracts

sensitivity_level PII > INTERNAL > PUBLIC

constraint pii_handling {

tool_output.sensitivity <= granted_scope.max_sensitivity

}

policy enterprise_ai {

all tools enforce pii_handling

all tools with sensitivity(PII) require human_approval

}CI/CD pipelines validate tool contracts against organizational policies before deployment. Tools that violate policy don't ship.

This approach aligns with a principle I call "coloring inside the lines"—a counterpoint to the prevailing agentic AI narrative.

The industry conversation around AI agents emphasizes autonomy, adaptability, and open-ended capability. Build agents that can figure things out. Let them tool around until they succeed. Trust the foundation model's judgment.

This narrative has produced remarkable demonstrations. It has also produced CVE-2025-6514.

Domain-specific languages are the natural expression of this philosophy. A DSL for MCP contracts doesn't make AI less capable. It makes AI capability legible—to developers, to security teams, to operators, and to the agents themselves.

The agent that knows its boundaries can work confidently within them. The agent operating on suggestions and best practices is one prompt injection away from disaster.

For teams interested in exploring this approach, here's a starting point. This Langium grammar defines a minimal contract language for MCP tool capabilities:

grammar McpContracts

entry ContractFile:

(capabilities+=Capability | tools+=ToolContract)*;

Capability:

'capability' name=ID '{'

(constraints+=Constraint)*

'}';

Constraint:

'constraint' name=ID '(' params+=Parameter (',' params+=Parameter)* ')' '{'

body=ConstraintBody

'}';

Parameter:

name=ID ':' type=Type;

Type:

name=('string' | 'int' | 'boolean' | 'path' | 'url' | 'json' | ID);

ConstraintBody:

expressions+=Expression ('and' expressions+=Expression)*;

Expression:

left=Operand op=Operator right=Operand;

Operand:

PropertyRef | StringLiteral | NumberLiteral;

PropertyRef:

root=ID ('.' path+=ID)*;

Operator:

'=' | '!=' | 'starts_with' | 'contains' | 'in' | '<' | '<=' | '>' | '>=';

ToolContract:

'tool' name=ID '{'

('requires' requirements+=CapabilityRef (',' requirements+=CapabilityRef)*)?

('param' params+=ParamDecl)*

'}';

CapabilityRef:

capability=[Capability] ('with' constraint=[Constraint])?;

ParamDecl:

name=ID ':' type=Type ('@' constraint=[Constraint])?;

hidden terminal WS: /\s+/;

terminal ID: /[a-zA-Z_][a-zA-Z0-9_]*/;

terminal STRING: /"[^"]*"/;

terminal NUMBER: /[0-9]+/;This is deliberately minimal—enough to express file path constraints, SQL read-only restrictions, and URL domain allowlists. A production implementation would add:

But even this minimal grammar, compiled through Langium, produces a working LSP with syntax highlighting, error detection, and auto-completion. It can generate TypeScript validators. It can produce JSON manifests. It's a foundation for real contract enforcement—not a research paper.

Organizations implementing MCP face a choice. They can continue adopting the protocol with ad-hoc security measures: input sanitization here, rate limiting there, fingers crossed that tool descriptions accurately reflect tool behavior. This path leads to more CVEs, more incidents, more compliance failures.

Or they can treat MCP's security delegation as an opportunity. The protocol's flexibility means organizations can define their own contract layer—one that expresses their specific security requirements, integrates with their existing governance frameworks, and provides verifiable assurances rather than documented intentions.

Langium makes that second path practical. Not theoretical. Not years away. Practical today, with tooling that runs in the same TypeScript ecosystem where MCP servers already live.

The MCP registry has 1,500+ servers. Microsoft, Anthropic, and major cloud providers are betting on the protocol. The question isn't whether MCP will see enterprise adoption. The question is whether that adoption will be secured.